#263 - CHARLES RENFRO, Partner at Diller Scofidio + Renfro

SUMMARY

This week Charles Renfro, Partner at Diller Scofidio + Renfro joins David and Marina of FAME Architecture & Design to discuss Charles’ childhood and early interests in architecture, his education and linking ideas of sexual freedom with architecture, joining Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio, becoming a partner at his office, his design philosophy, how New York has changed, and more.

ABOUT CHARLES

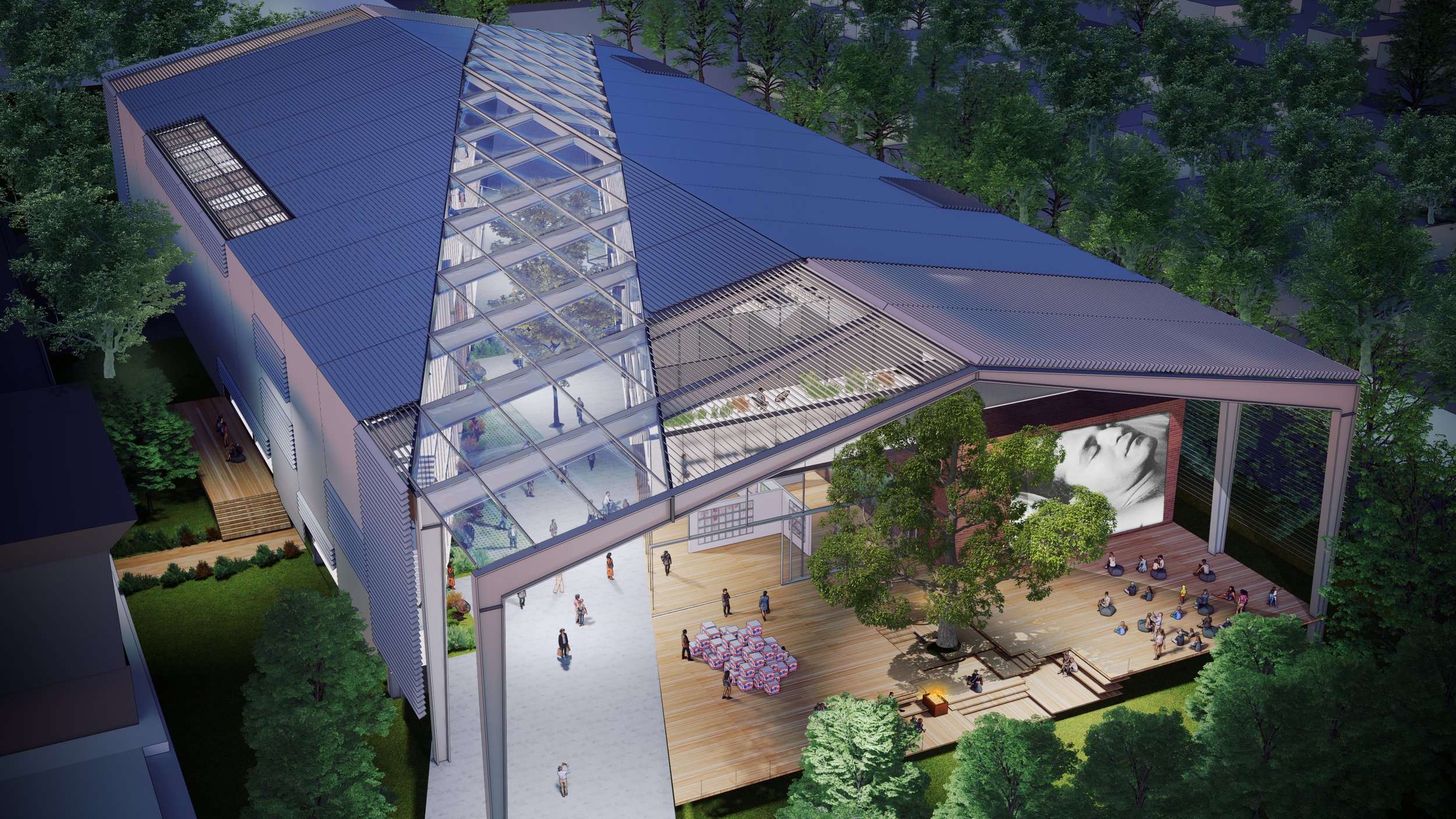

Charles Renfro joined Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R) in 1997 and became a Partner in 2004. He has led the design and construction of the studio’s first public park and first concert hall outside of the US: Zaryadye Park, a 35-acre park adjacent to the Kremlin, Red Square, and St. Basil’s in Moscow, and the Tianjin Juilliard School in China. Charles has also been the Partner-in-Charge of many projects in the studio’s academic portfolio, with projects completed at Stanford University, UC Berkeley, Brown University, and the University of Chicago, with two new facilities under construction at Columbia University. Charles is currently leading the design of two projects in his native Texas: the renovation of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Kalita Humphreys Theater in Dallas, and a new Visual Arts facility for his alma mater, Rice University, in Houston. Charles is the Co-President of BOFFO, a nonprofit organization that presents innovative and experimental art and design, and has twice been recognized with the Out100 list. He is a faculty member of the School of Visual Arts.

HIGHLIGHTS

TIMESTAMPS

(00:00) Charles’ early interests in architecture, growing up gay in a conservative area, and how passion is related to fear.

“In fourth grade for a period of several months, Raymond Mayfield (my classmate) would tell me in second class, “I’m going to beat you up today.” And I said, “Okay.” And he said, “Okay, I’m going to beat you up after school.” This happened for months. And then finally, you know, it got so… I didn’t want to tell anyone. I was too proud to do that. Finally, I told my mom and she stood up for me. She went over to Raymond Mayfield’s house, talked to his parents, and got back the radio thing he had stolen from me one on of these particular occasions. After that, I was so humiliated that I said to her, “I’m too embarrassed to go to school.” She said, “What do you want to do?” I said, “I want to go see buildings.” And she said, “Okay, where?” I said, “Okay well I want to go see Greenway Plaza, the Galleria, Penzoil Place.” I was in fourth grade! So that would make me, like what, nine? I rattled off all of these recent buildings that had been built in Houston by architects like Phillip Johnson, HOK, Gordon Bunshaft […] I just wanted to see the city booming. And so for two weeks, she took me out of school and we drove around in her big old fat Cadillac and went to see all the buildings in Houston.” (04:33)

“Somewhere deep down I knew that if I somehow could be involved with the making of places, that there was power in that. And I felt kind of powerless in elementary school in Baytown Texas, growing up gay… and I didn’t admit I was gay until basically at the end of high school. I had to pretend to be somebody I was not. But the architecture, whether I acknowledged it or not, definitely helped me think about a future where I was more in control and could do things that pleased me. And I wasn’t just going to be a victim because of who I was.” (07:38)

(14:24) Exploring sexuality and freedom in the design of spaces. Studying architecture at Rice University

“I started actually linking spaces of freedom—sexual freedom or just personal freedom—with my work at Rice. So by the second year, if the assignments were open-ended enough I would start to interrogate issues of social norms and the spatial conditions around alternative lifestyles. I remember some parents of my classmates and saying, “Wow. This project really stands out. This is not just a ‘what makes a good place’.” That was actually the name of the assignment. Everybody [other students] said a bench with a tree over it or this or that. I said, “A double-height dance floor with a stair that connects the dance to the upstairs because that activates people and it makes you be passive and it can put on stage or it can take you off stage.” So the idea of a life lived theatrically and comfortably and confidently around one’s sexuality started to take root in my work.” (15:40)

(24:00) Charles on playing the clarinet.

“There’s something really fabulous about playing with a group of people together. I really miss that. That’s exhilarating… that a hundred people are doing do the same thing together. It’s a wonderful experience.” (29:33)

(31:55) Working in New York after undergraduate school. The importance of learning how things are built. Being involved in the art world.

“At DS+R, we do work that ranges in scale […] we’ve designed drinking glasses and we’ve designed islands in the ocean. Design thinking, I think, comes from the same place whether it’s large scale or small scale. But design detailing… like, knowing how something gets put together when it gets down to that comes from knowing materials and having built things.” (35:36)

“I actually ran my own practice alongside my tenure at Liz and Ric’s for a couple of years before deciding to give those small potatoes jobs up, when things like the ICA in Boston came in.” (39:52)

(41:51) Joining Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio and the office’s early work.

“We hope that after someone visits one of our projects […] that they’ll be a different person and they’ll have been affected by the experience in these buildings. And that the things that these buildings present—let’s say art or in the case of the Highline, the city—that the way that these projects present their contents… because the contents in our projects are not the project themselves, the contents are always something else. There’s always something outside the physical thing that’s being presented. So the hope is that when people go through our project that that content has shown through more brilliantly than it might otherwise have.” (55:24)

(57:19) Becoming a partner at DS+R. The names of offices.

(01:03:34) The philosophy and work of DS+R.

“The thing that links all of the projects is the analysis of the problem of the project and to make that problem—and when I say problem I mean, something we’re looking at, something we’re pushing, something we’re investigating—have the problem become a central feature of the building and try to make the problem rise as the thing you read primarily in the architecture. To not make a collage-y building, but try to make a building with integrity that’s all working on this problem.” (01:07:00)

(01:19:30) Communicating architecture to clients and the general public. The Shed in New York.

(01:26:05) New York City’s culture and changes.

“I don’t like how expensive the city has become and I think there’s a huge housing problem. Huge. And I think there should be totally so much more regulation and I also think there should be many more ways to make housing in the city including by remaking all of the office buildings that are being evacuated in all these monoculture districts, such as midtown. Remake them into housing. Change the codes, change the zoning, get the engineers in, put parks in them, put elementary schools, put store, put low-income housing, put high-income housing. Mix it all up! Make new kinds of buildings in the city. That’s the opportunity I see right now that would make this place be for me as exciting as it might have been for some people in the 70s.” (01:30:33)

(01:33:09) Favorite buildings.

“I will say that cities as organisms are the most exciting to me more than even architecture. In that regard, Rio De Janeiro of all the cities I’ve been to—and I haven’t been to all the capital cities, but to most of them— Rio De Janeiro is unparalleled. I believe that is a piece of exquisite architecture which combines nature, landscape, people, sexiness, and sun, and all of this stuff in such an exquisite way.” (01:34:55)