#102 - WES JONES, Architect an Director of Architecture at USC

SUMMARY

DESIGN, HONESTY AND HUMOR

This week David and Marina are joined by Wes Jones, Founder of Jones, Partners: Architecture and Director of Architecture at the University of Southern California, to discuss honesty and humor in design, USC's architecture program, bad design reviews, his solution for solving the homeless crisis in Los Angeles and more. Enjoy!

ABOUT WES

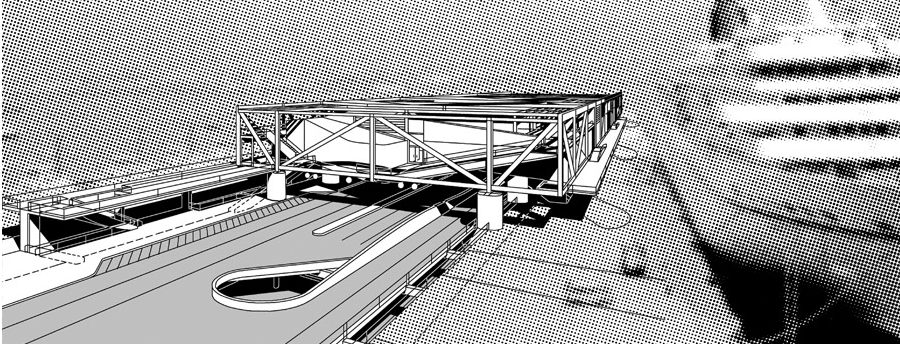

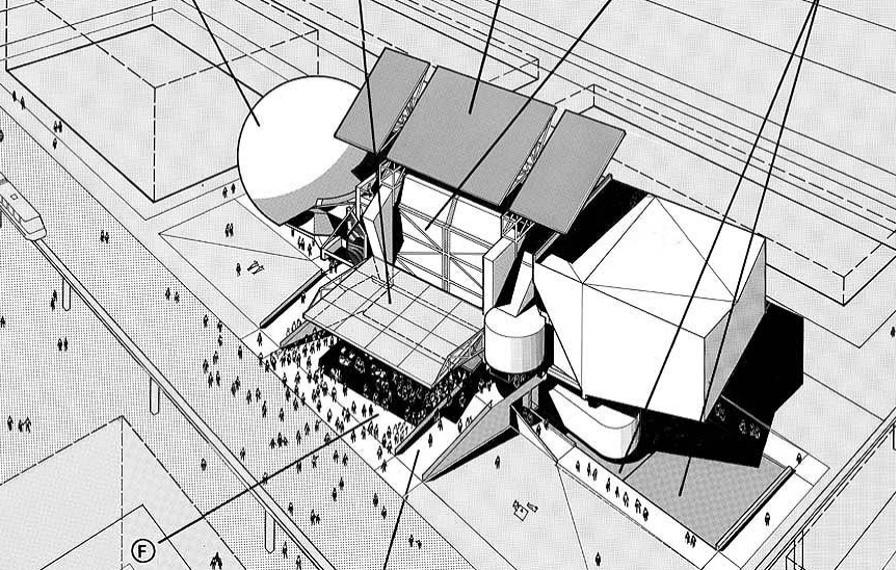

Wes is an American architect, educator and author. Founding partner of Holt Hinshaw Pfau Jones, in 1987 and then Jones, Partners: Architecture in 1993, Jones is a leading architectural voice of his generation, advocating for a continuing appreciation of the physical side of technology within a world increasingly enamored of the virtual. For most of his career this has taken the form of an overt fascination with mechanical expression, both static and moving, and his designs have been celebrated for their "engaging operability” and humor. In his early writings he focused on making the case for the appropriateness of mechanical form in architecture, but his later essays have also taken on more fundamental disciplinary questions, particularly with respect to the growing hegemony of digital design.

HIGHLIGHTS

TIMESTAMPS

(08:30) Honesty, humor and responsibility in Architecture.

“…Architecture’s ethical foundations as an activity engaged in, or a good produced by, a relatively few […] with a responsibility to support the many. This is part of what makes architecture a profession beyond simply the need to secure issues of life safety and that sort of thing. If we have this responsibility to place people in the world and we are exercising this responsibility as a few, then somehow we have to earn the right to exercise that responsibility through our study, through our experience, through ultimately caring about what we're doing. We have to be earnest in that. Somebody told me once architecture is the most optimistic art because of the expenses involved and because of the responsibility it holds in that regard. So, humor then becomes a way of diffusing the angst and weight of that responsibility a little bit, a way of coping with it. And also humor has a naturally sort of critical quality about it.” (09:26)

“Architecture as distinct from engineering is not a quantifiable enterprise. It's not an objective fact. It's not frankly a necessity. So we're operating in a situation where we act with a sense of absolute necessity and the incredible importance of what we're doing. Yet at the end of the day, it's a totally elective phenomenon, and we're ever... I was about to say we're ever conscious of that, but in fact, actually we need to be reminded of it. And humor helps us to remember that.” (13:30)

(25:00) Wes on Teaching and Architectural Theses in Academia.

(36:40) Wes on mastery versus innovation in society and design.

“What I've found is that there is within our culture as a whole an assumption or a privileging of novelty and originality over almost anything else in any creative endeavor. We're not particularly interested these days in excellence or mastery. We don't allow any particular effort to mature. The effort that is matured is already passé and yesterday. It is—the term we use now—is history. That's history. It's old news. We don't care about that anymore. So consequently, the effect is that almost everything interesting we do never gets to a mature and perfect itself. So it's always flawed. It always has problems and it's not always the best example of what it is proposing to the world because we just don't let it live.”

(43:39) Defending your Architecture

“I said, ‘So, come on, level with us. You're an architect. What we see is this on the wall […] Tell me, why does it look like that?’ And his answer, which just a total surprise to me, was, ‘I'd rather not talk about it. It's personal.’ …and I just went off and I said, ‘Are you kidding? You're an architect. You have a public responsibility to stand up for your work and tell us why it is the way [it is]. That's how you earn the right to a foist on us.’ And what was most amazing was that all the critics rally to defend the kid.

(50:19) Why Architecture is not a necessity and What Architecture means to different generations.

“Architecture as an elective phenomena has no objective validity or truth and therefore each generation's going to be responsible for understanding architecture in its own way for defining architecture. And it is each generation's responsibility to care enough about what they're doing to want to pass on what they believe the truth is to be to the following generations. But the following generation isn't obligated to accept that to follow that they have to make up their own minds for it. And consequently you could say that it's frankly a miracle that architecture has survived at least in any kind of recognizable form, or at least in any way that's recognizably related to previous generations of architecture because of that. And we are definitely seeing that it seems to me, far greater generational changes—both technology driven and culturally driven—now than at any time in the past, where the changes seemed to be more gradual and spans several generations. And so the idea that these things we're talking about—that architecture matters in the way that we're talking about, that it has a sense of responsibility—in a way, could be understood as a generational thing totally at risk, therefore.” (51:42)

(53:32) Generic and Iconic Architecture.

“Society needs a few people like [Frank Gehry] who to create the monuments and that sort of thing. But if you try to imagine an entire city filled with Disney concert halls, I don't know that that really is a good way to live.”

“It's a very important point of ours that all architectures should aspire to become a vernacular, should aspire to be generalizable. You should be able to create a city out of your form and your form should be capable of supporting that—which is a distinction I would again place between work like ours and somebody like Gehry. So architecture has this conflict between wanting to stand out and be unique but also wanting to be generalizable and replicable and exemplary.” (01:09:04)

(01:03:00) Consistency and evolution in Architecture projects.

"You hear from some architects and certain well known practices who do at a different thing every time—and they pride themselves in that—say, ‘We're doing something specific to this client.’ But, I would then a counter that by saying, ‘So in other words, you haven't learned anything from your previous work.”

(1:10:39) Technology in Architecture.

“We want to use technology specifically as a medium for engaging the world rather than distancing us from the world […] rather than it happening unthinkingly or magically […] So, I have an issue with a lot of the technology now where you have wearable sensors or whatever and the lights follow you through the house or the temperature changes without you asking it too, just because it's trying to make life easy for you without you having to lift a finger. And that to me points in the direction of the people in that movie, Wally… which is just an awesome film.”

(01:15:47) Wes on his upbringing and life influences on his work.

(01:17:00) (01:50:30) Solving the homeless crisis.

“We have a way of solving the homeless problem within a year; all 50,000 units that we need. At a cost that's less than a fifth of what the city is paying now for dormitory-style accommodations, we can provide private accommodations to the homeless people.” (01:23:12)

(01:34:12) UC Berkeley and West Point and their impact on Wes’s work and philosophy.