#133 - DANA CUFF, Founding Director of cityLAb

SUMMARY

URBAN DESIGN, CHANGING PLANNING POLICIES AND SMART ARCHITECTURE

This week Dana Cuff, Winner of Architectural Record’s 2019 Women in Architecture Activist Award, Founding Director of cityLAB and Professor of architecture and urbanism at UCLA joins David and Marina of FAME Architecture & Design to discuss the challenges of changing state policies, combining urban design and research, why smart architecture hasn't quite revolutionized the design world, life stories of orange groves and living in Sweden, and more. Enjoy!

ABOUT DANA

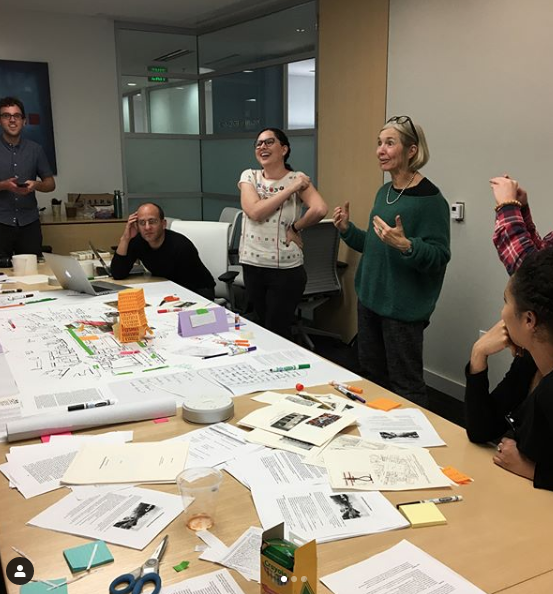

Dana Cuff is a professor, author, and scholar in architecture and urbanism at the University of California, Los Angeles where she is also the founding director of cityLAB, a think tank that explores design innovations in the emerging metropolis.

Since receiving her Ph.D. in Architecture from UC Berkeley, Cuff has published and lectured widely about postwar Los Angeles, modern American urbanism, the architectural profession, affordable housing, and spatially embedded computing. Two books have been particularly important: Architecture: the Story of Practice which remains an influential text about the culture of the design profession, and The Provisional City, a study of residential architecture’s role in transforming Los Angeles over the past century.

Her urban and architectural research now span across continents to Sweden, China, Japan, and Mexico. In 2013 and 2016, Cuff received major, multi-year awards from the Mellon Foundation for the Urban Humanities Initiative, bringing design and the humanities together at UCLA.

HIGHLIGHTS

TIMESTAMPS

(00:44) Founding cityLAB

(09:00) Utopias and city typologies

“To me, that's what architecture does best; it lays out a vision of what might be the next kind of incremental change in the city or transformation of the city that other people can’t imagine, and then we can aim towards it. So I'm an anti-utopian and an anti-incrementalist, actually. Those are the things that are usually posed against each other.”

“You're right that Los Angeles doesn't have a single urban construct. It’s what lots of others of people have called an urban architecture without urbanism. [ . . . ] Look at Grand Avenue, the sort of attempt to make an alternative downtown. It's just a string of buildings. It's hardly even held together by a street. So, what does it mean to have urbanism here? Some people would say that that's exactly the kind of place you need a grand master plan, which I sort of think of as the same as a utopian model. And to me, those have never worked. They might serve as narratives, right? They work perfectly in science fiction or in a book-like utopia. But for actual implementation, no one ever even implements a master plan. It kind of sets an abstract ideal and you aim in that direction. I think this is where architecture and architects play a role in building something as a demonstration that shows what you should do next or what might happen next. So that's what I would call a ‘radical increment’: an architectural intervention that has a DNA that can spread.”

(16:19) Doubling the density of Los Angeles and rewriting planning policy

“Property owners that came to meet with us would say, ‘We own our homes. We borrowed out of them to send our kids to college. Now our kids can't come back and they don't want to live in a condo and they don't want to live in some old traditional thing. We want to attract them to come back, but we want to build new kinds of spaces for them. They would live in our backyard but not in the house.’ So, it started to just become a logic. Everybody basically had a backyard home story: If you had a backyard, you wished you had a way to settle some caregiver, nanny, an adult child returning, yourself so that you could live in a smaller space and rent out your house and get better income.” (51:24)

“In the case of the ADU bill, 8.1 million single-family properties in California now can have a second unit. It's actually shifted the man's home as his castle into something we share. I feel like it's a metaphysical change. And of course, it could produce more housing than any other single mechanism. It was a group of women behind the scenes of two state legislators that were personal connections that came together to make this…”

(21:59) Urban thinking and social/political missions in architecture

“I'm done with architectural autonomy. Like, enough already. I think the discipline goes through phases and for a long time we really strengthened the discipline… That was when the theory was really the major counterforce to practice and Peter Eisenman and Tony Viddler battled it out like a wooly mammoth against a saber tooth tiger. I like them both but still, that's 40 years ago. We don't need to do that anymore. The discipline… maybe we'll go back to that in another 20 years. But right now, what we need to do is situate the discipline in the global landscape; in the landscape of the city. There's so much work to be done. It's immoral that at least a piece of what our profession isn't dealing with that."

(43:06) Living in Sweden, family orange groves, and urban policy

"Now when global warming and the housing crisis are in everybody's front page, local news, evening news over breakfast, it seems to me firms recognize the intersection between work and the conditions of the world. Most architects now would love to get into affordable housing even though there's not much money to be made as an architect in an affordable housing project because they're so complicated. Still, there's so much work that needs to be done. People see that as a growing market. I'm all for when market and issue intersect.”

(53:33) Using schoolyard sites for affordable housing

(56:37) Convincing community and government constituencies to approve projects

“My new principal is incentivizing at the highest levels, like from States, and customize at the local level. So instead of giving people the authority at a local level to say, ‘Yes, we'll build housing at our school’, the State says, ‘If you build housing at your school, you will get ‘X’: extra funding for the community rooms, subsidized lunches, or whatever the state can use to incentivize… So there’s still some kind of local participation, but it's not control. And that puts me at odds with a lot of the people who have the same kind of political affiliations that I do, which are progressive or radical. [. . . ] I’m actually at the moment feeling like local control is a local barrier. We can't remove participation at the local level, but we can’t ”

(01:02:45) Dana’s career path and architecture’s need for new business models

(1:14:30) Smart Cities and “Urban Sensing”

“We were trying to create cities [in which] you could do political shopping. This was maybe 10 years ago, where you would see a jacket and you could then scan whether or not it had animal rights, child labor, where your money went, how much profit they were making. And that information is there; you could get it right off of a UPC. We were trying to imagine what it would be like if you could actually enable your politics spatially in the environment. That might also be like sensing when your biomechanics are being monitored: If you go to a stadium now, there are biorecognition systems that are operating and we're not aware of them. How do we make people aware of the surveillance state that's operating?” (01:15:18)

“There were lots of questions at the time that seemed like a bubble. Like the smart city stuff. In Sweden, for instance, they had a mechanism that they were putting in cars that would slow the car down to the speed limit that was posted. So the roadways and GPS allowed them to monitor speed and the Swedes that were in the test like it. […] You could make a safer street. You could make energy from the way the cars traveled. All that seemed promising to me at the time.” (01:18:39)

“One of the things that seem true to me, even from with the smart city stuff and the pervasive computing, is that I thought it would have real impacts on the form of the city, that architects would end up being involved. It turned out it was kind of like a thermostat; that doesn't change architecture. It's smart. It makes the world more comfortable. It’s a good thing, but why do I care that my front door could be activated by recognizing me through my eye and not turning a lock. It just doesn't have very many formal implications. And so far I think that's true with autonomous vehicles too.”