#160 - GREGG PASQUARELLI, Architect and Co-Founder of SHoP Architects

SUMMARY

THE WORLD’S SLIMMEST SKYSCRAPER AND NEW YORK CITY

This week Gregg Pasquarelli, Architect and Founding Principal of SHoP joins David and Marina of FAME Architecture & Design to discuss designing the world's slimmest skyscraper, modernism and provincialism in New York City, the most important part of creating architecture, 30-minute elevator pitches, city development, favorite restaurants and more. Enjoy!

ABOUT GREGG

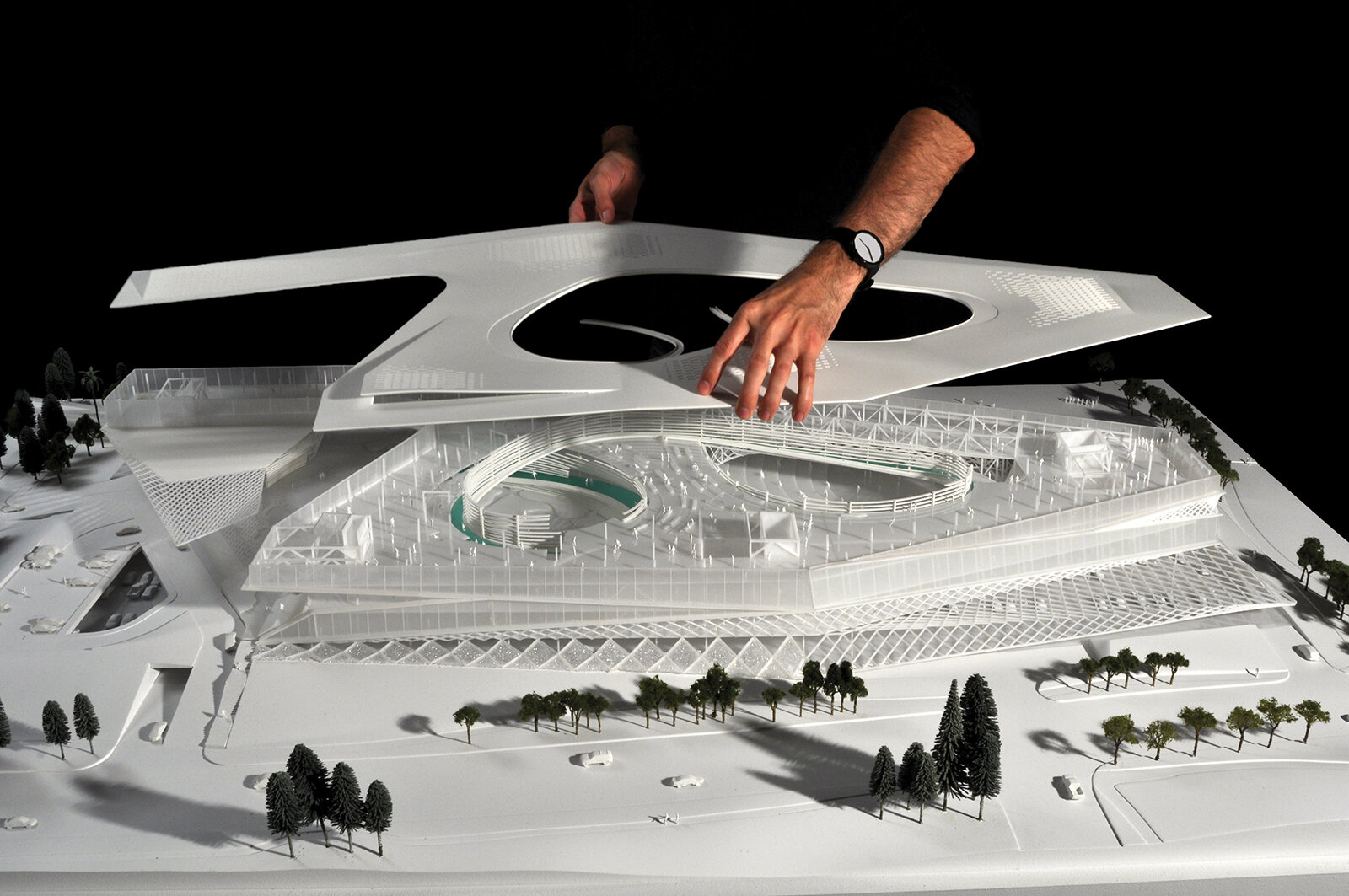

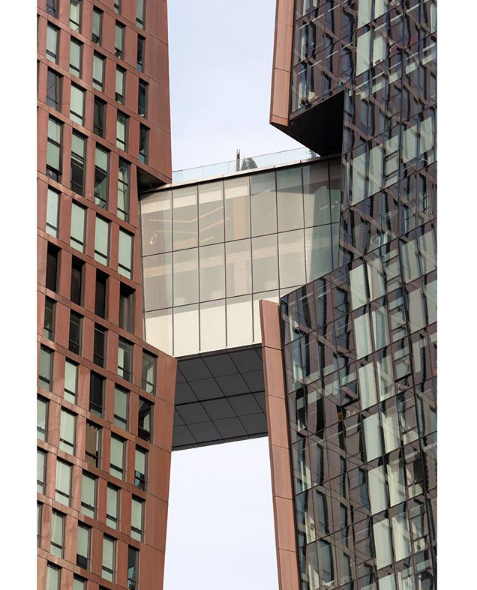

As a founding principal, Gregg Pasquarelli has been at the center of SHoP’s collaborative practice for over 20 years—leading teams in design, master planning, and real estate development. He has served as lead partner on many of the firm’s most prominent projects, including The Porter House, the Barclays Center, Pier 17 and the East River Waterfront esplanade, 111 West 57th Street, and the American Copper Buildings. Beyond the studio, Pasquarelli has earned a reputation as a thoughtful leader of his generation of innovative architects and a powerful advocate for design quality and community values in contemporary city-building. His dedication to moving the profession forward continues in his commitment to lecturing and teaching, where he brings SHoP’s message—about the unity of technological invention, artistic inspiration, and public responsibility—to students across the country and around the world. He has lectured and published globally and has held chaired professorships at schools such as Yale University, Columbia University and The University of Virginia, among others.

HIGHLIGHTS

TIMESTAMPS

(00:00) The value of lecturing and knowing how to speak with clients about business.

I think that there was a generation or two of architects that proceeded us that thought that somehow engaging in those kinds of [business] conversations was doing a disservice to the purity of architecture. And that is complete and utter bullshit. Complete. And in fact, what we have found is that the more engaged we are with those other things, the more architecture we can do. (11:54)

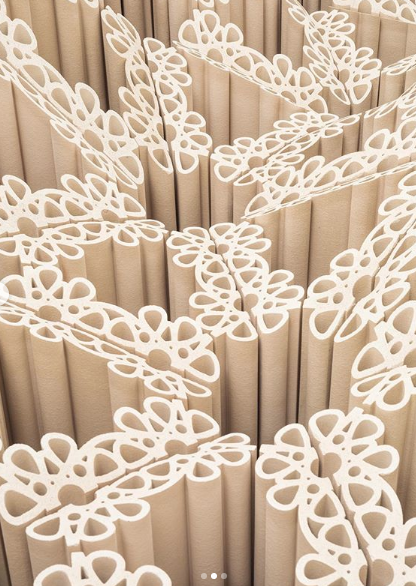

(14:34) Having an architecture office without a singular ‘brand identity’

I would never presuppose to sort of force a kind of aesthetic or a solution onto a client. It only comes from the relationship between you and the client and working through and the team and the city you're in and the current political climate. It's that sort of cauldron, those intense forces, that come together and you birth this new thing. (15:29)

Probably the most difficult thing for shop is like we, we can't be understood in an elevator pitch. It's, it's too complicated of a story in a way. Very often we hear, “You sent in your book when we were looking at 30 architects and I didn't really understand it.” And then every time we go in and have the conversation for a half an hour or an hour, they're like, “Oh, I get it now. This is awesome.” (17:16)

(21:43) The most important part of architecture.

I think what we've learned in 20 years is that relationship is worth more, is more important than the program or the budget or the prestige of the commission. It's really about finding the right partners to work with, both in terms of businesses worth it, but also just as a human being. […] We're sort of halfway through our career right now and I would say the second half, that’s what's most important to us and that we see the best projects that we've done [were] the were the result of the best relationship with the client no matter what it was. (23:17)

(25:27) The evolution of their office (from 5 partners to over 200 designers and architects) and their ‘Don’t Be An Asshole Rule’

We got up to around 230, 240, 250, something like that and we didn't like it. It wasn't working. So we actually purposely shrank the firm over the next few years back down to about 160 and then got all the systems in place to really have the office run as an enterprise, like a well oiled machine. We've been very careful in growing the firm again, but it's on an upward march. (33:48)

(38:55) How New York can be strangely insular when it comes to architecture.

I will say that late modernism in New York became a very insular environment and New Yorkers, for being as worldly as they are, are actually somewhat provincial in the sense that if it didn't happen on the Island of Manhattan, it doesn't count (40:40)

But the thing that opened New York up again to looking at the world was 911. It was exactly what happened. I think that New Yorkers didn't know that they didn't have the best architects in the world working there. And then when the competitions for the rebuilding of the trade center started and many of the European architects came in, it lit fire like under everyone. [New Yorker’s] were like, “Oh my gosh, you mean we don't have the 10 best architects in the world? And nine of them aren't in New York?” (42:07)

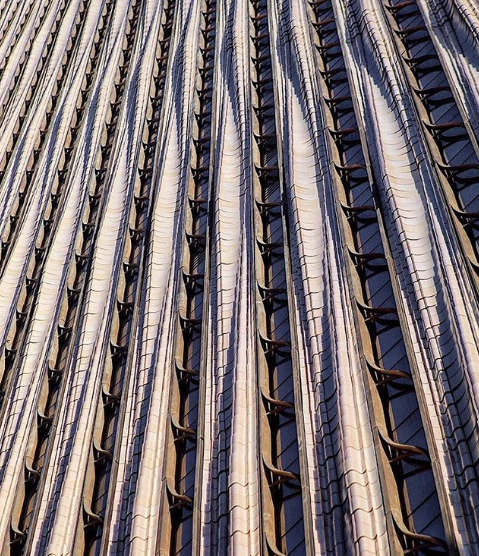

(44:27) Gregg discusses 111 W57 (the slimmest tower in the world) and what it is like to have built projects in his childhood city.

That building—111 West 57th street—it's that partnership with the client at the right time, engaging technology, engaging politics, and that commitment to making something so beautiful and then being able to it… It's a hard building to build and hard building to finance and everyone stayed committed and focused for the five or six years that we've been working on it and it's going to be another one or so until it's done. So, just to see it turn out as well as it's turning out… It's just like, “Fuck Yeah!” (56:06)

(56:57) Luxury high-rises in New York City and the city’s financial inequality.

The second any city puts incredible limits, like height limits and type limits and not-as-of-right zoning, that’s the day the city is dead. Everyone complains about the cost of living in San Francisco. Well, you know why? Because you put height limits on everything and every approval of every building is discretionary. That's why it's so expensive. (59:27)

I would be very sad if New York changed its view of that we're ready to embrace the future as opposed to embalming it and its past. And those super-talls are a symbol that the city is healthy and growing, and people are trying and they're experimenting. (01:00:47)

(01:03:01) The evolution of New York and why Gregg loves it.

Architecture’s hard… Architecture’s hard, and no matter how tired you are or exhausted you get, out on that street and there's a palpable energy. You see the dreams in people's eyes and you see the willingness to work really hard and you see that everyone is negotiating every economic strata, every racial strata, every educational strata. And it's cool. It’s like, “We’re here and let's go do it today.” (01:06:41)

(01:12:46) What makes SHoP a “New York office”

It goes back to the “both/and.” It’s the “high/low.” It's the being hard-nosed and practical, and an absolute dreamer at the same time, being an entrepreneur and an artist at the same time. Taking risks, pushing the limits, not accepting standard forms of practice, and saying, “It doesn't have to be this way just because we've always done it this way. Let’s reinvent it. And if it's a bad idea, we should fail and be punished. And if it's a good idea, we should succeed and be heralded.” (01:13:02)

(1:15:16) How the profession should change to be more lucrative

I think it's very silly that we sell our time by the hour—we sell our intelligence or creativity by the hour—because probably a lot of hours are worth about 30 bucks and then some hours are worth 30 million. Could you imagine if we paid musicians like pop stars by the hour? “Taylor Swift, we'll pay you $1,000 per hour for that hit song you wrote.” It's the most ridiculous thing ever. So, I think that that's not a great business model. (01:16:28)

(01:19:05) Gregg answers the question, “Does SHoP still feel like a young, edgy office, despite it being over 200 people in size and decades-old?”